We use cookies to make your experience better. To comply with the new e-Privacy directive, we need to ask for your consent to set the cookies. Learn more.

From literary drink to popular drink

10th to 14th century

The tea fights

In the Tang Dynasty, tea was so popular among writers that there were regular tea banquets where writers met to think up new poems about tea. In the Song Dynasty (960 - 1279), such intellectual meetings degenerated into a kind of tea competition. Among the rich, it was a fashionable pastime to hold tea competitions. The tea contests originated at a time when the various tea-growing regions were competing for the emperor's favour. To select the best tea, the emperor had the teas compete against each other.

An ink painting from the late Song Dynasty depicts the scene of a tea contest. The gentleman on the left in the foreground holds a tea cup in his hand. The boy behind him is just pouring from a pot into another cup, which is probably meant for the gentleman on the right in the foreground.

An ink painting from the late Song Dynasty depicts the scene of a tea contest. The gentleman on the left in the foreground holds a tea cup in his hand. The boy behind him is just pouring from a pot into another cup, which is probably meant for the gentleman on the right in the foreground.

The competition looks something like this: A small piece of a tea cake is broken off and ground into powder and placed in a special porcelain bowl (see figure below), then a small amount of boiling water is poured on. With a small bamboo broom it is beaten into a thick mass. More hot water is added to the bowl and stirred further until the bowl is about half full. By stirring, the tea foamed strongly. It was exactly this froth that was the focus of the competition: the colour of the froth should be a fresh white colour, which is why black porcelain bowls were so common in the Song era.

A porcelain tea cup from the late Song period. It has a dark brown, almost black glaze. This dark glaze was especially popular in the Song period because of the tea fights.

A porcelain tea cup from the late Song period. It has a dark brown, almost black glaze. This dark glaze was especially popular in the Song period because of the tea fights.

Another porcelain tea cup from the late Song period. The black glaze is even darker.

Another porcelain tea cup from the late Song period. The black glaze is even darker.

The black shell brought out the white colour of the foam best. The foam should also cover the entire surface of the infusion and adhere firmly to the bowl. The longer the foam was left standing, the better the tea should be. To have a possible idea of this kind of tea serving, you only need to look at a Japanese tea ceremony today, because Japanese monks brought it back to Japan from their study visits to Chinese monasteries in the 11th-12th century. Similar to a bad student who never dared to deviate from his master's instructions just by a hair's breadth, the Japanese still practice this ceremony today almost unchanged as they did during the Song period.

Emergence of the teahouses

The growing popularity of Buddhism caused more and more believers to flock to the monastery. The believers also adopted tea drinking as part of their daily domestic meditation. The innumerable books, texts and poems that the writers wrote about tea further reinforced this trend. Already in the Tang period there were shops that offered tea as a thirst quencher. Real tea houses were only built in the Song Dynasty, when urbanisation began. In the big cities the strict separation between market and residential areas, which was common before the Song era, was abolished. Restaurants and theatres were opened in the middle of busy residential areas. For the first time there were also restaurants specialising in tea.

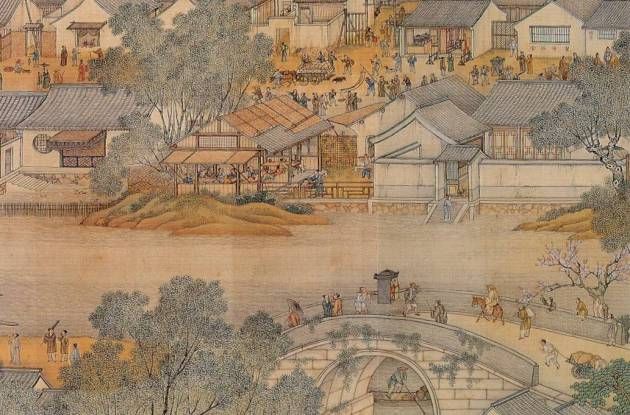

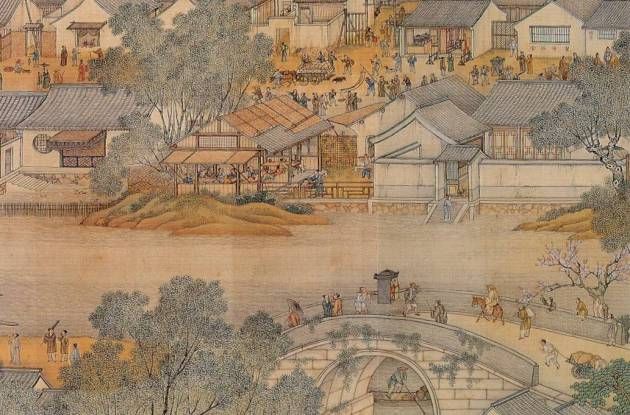

This famous painting from the Song Dynasty depicts the Song capital Bian Jing on a spring day. The whole painting is 5.3 m wide and 2.5 m high and contains over 500 people. In this detail you can see an open tea house directly on the shore and between two inhabited houses.

These teahouses (see picture above) often had a tea ceremony master, called a "tea doctor". Depending on the target group, the tea houses were furnished differently: For intellectuals there were teahouses decorated with cut flowers, calligraphy and paintings; for the common people the teahouse became more and more a multifunctional meeting place. Street performers performed, gossip stories were exchanged, disputes among neighbours were settled, business was done, prostitutes offered their services.

This famous painting from the Song Dynasty depicts the Song capital Bian Jing on a spring day. The whole painting is 5.3 m wide and 2.5 m high and contains over 500 people. In this detail you can see an open tea house directly on the shore and between two inhabited houses.

These teahouses (see picture above) often had a tea ceremony master, called a "tea doctor". Depending on the target group, the tea houses were furnished differently: For intellectuals there were teahouses decorated with cut flowers, calligraphy and paintings; for the common people the teahouse became more and more a multifunctional meeting place. Street performers performed, gossip stories were exchanged, disputes among neighbours were settled, business was done, prostitutes offered their services.

This famous painting from the Song Dynasty depicts the Song capital Bian Jing on a spring day. The whole painting is 5.3 m wide and 2.5 m high and contains over 500 people. In this detail you can see an open tea house directly on the shore and between two inhabited houses.

This famous painting from the Song Dynasty depicts the Song capital Bian Jing on a spring day. The whole painting is 5.3 m wide and 2.5 m high and contains over 500 people. In this detail you can see an open tea house directly on the shore and between two inhabited houses.

Tea cultivation in the Song Dynasty

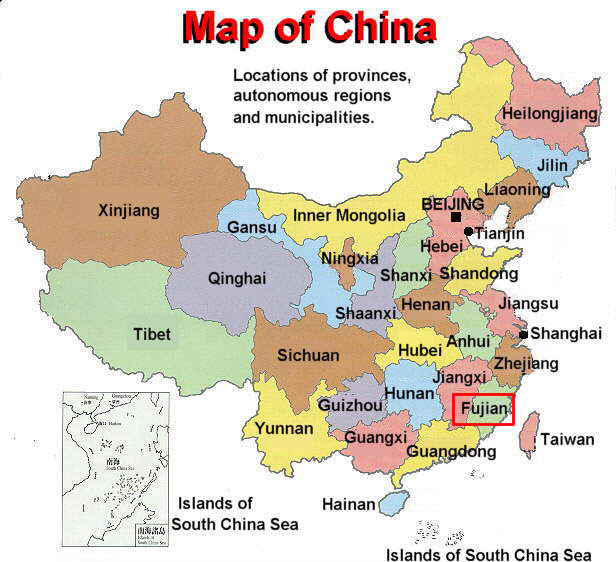

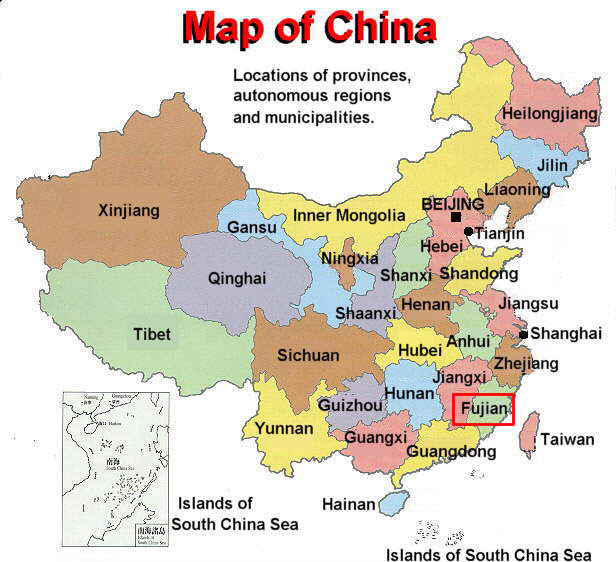

The Song period was much colder than the Tang period, so the growing regions shifted to the south. The best tea now came from a region in what is now

Fujian

Fujian

province (south-east China).

province (south-east China).

Fujian

Fujian

The change of direction in the production of tea

There was an important change of direction during the Song era. Tea was still mainly processed into pressed tea cakes.

But as tea became more and more a popular drink, the complicated preparation with the tea cake was no longer up to date.

Therefore, more and more loose teas were produced, which had the advantage that one could make tea quite quickly and easily.

The production of loose teas was also much easier than the production of tea cakes. Loose teas (green tea in today's sense) already existed in the Tang period and was mentioned in the

book by Lu Yu.

However, they had only gained importance in the Song period. At the end of the Song period and during the Mongolian rule (1271 - 1368) the production of loose teas surpassed even that of tea cakes.

In the Encyclopaedia of Agriculture of Wang Zhen (first printed in 1313, one of the 100 most influential books in Chinese history), the method of producing pressed tea was mentioned only very briefly,

whereas the production of loose teas was described in detail.

The pressed tea became more and more a marginal phenomenon, also in the literal sense: the main consumers of pressed tea were the marginal peoples of the central empire, mostly nomads or semi-nomads, who exchanged the coveted tea for horses (see also "The black tea").

The pressed tea became more and more a marginal phenomenon, also in the literal sense: the main consumers of pressed tea were the marginal peoples of the central empire, mostly nomads or semi-nomads, who exchanged the coveted tea for horses (see also "The black tea").